Slide Show - Diagnosing IBD

Click here to take our SURVEY

Your feedback is important to us! We will use your feedback to develop future areas of content about IBD which will help other patients, caregivers and families.

Diagnosing IBD

*Please note: This slide show represents a visual interpretation and is not intended to provide, nor substitute as, medical and/or clinical advice.

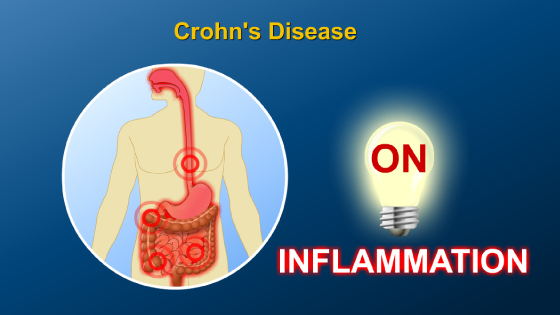

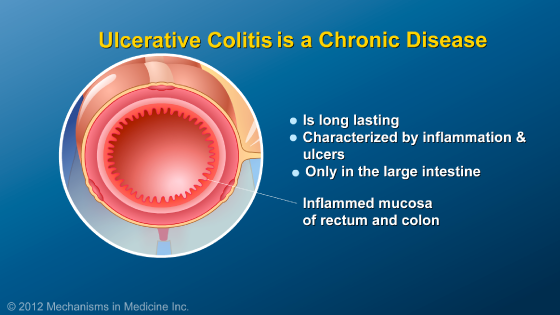

Symptoms of IBD vary according to which part of the intestinal tract is involved. These symptoms often wax and wane over time.

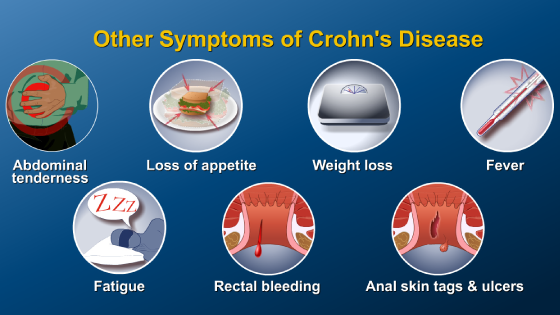

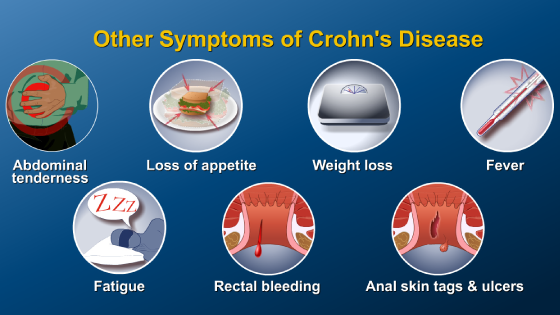

Symptoms may include stomach pain, bloody diarrhea, loss of appetite, urgency, constipation, rectal bleeding, fever, anemia, nausea and vomiting.

Symptoms not associated with the GI tract may also be present, such as arthritis, skin conditions, liver and kidney disorders, and inflammation of the eye.

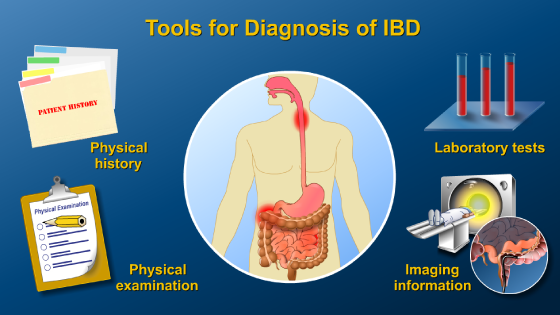

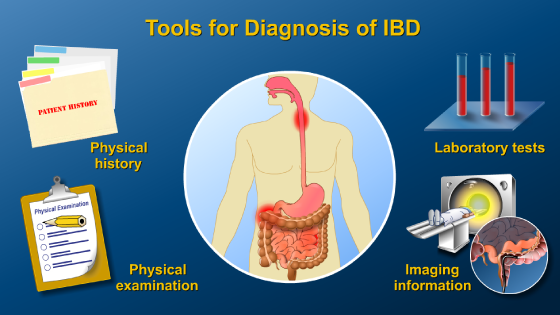

Diagnosis of IBD is based on a combination of physical history and examination, laboratory tests, and imaging information. There is no single test that will diagnose or rule out IBD. Several tools are used in combination to differentiate not only the type of IBD, but also the extent of disease involvement and prognosis (prediction of the course and outcome of IBD).

First, the physician takes a thorough patient history.

Next, a physical exam is performed to look for abdominal masses, tenderness or pain, a fast heart rate, fever, urgency, or weight loss. Slow growth or development, particularly in children, may also be present. The physician also performs a perianal examination.

A stool examination is done to rule out bacterial, viral, or parasitic infections.

A fecal occult blood test detects small traces of blood in the stool that cannot be seen with the naked eye.

Blood tests are important tools to aid in the diagnosis. A complete blood cell count is done to look for inflammation, anemia, or nutritional deficiencies.

Other tests may be done to look for signs of inflammation in the body. These include the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) blood tests, and the fecal calprotectin stool test.

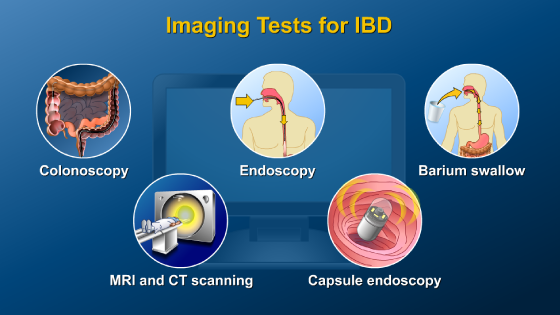

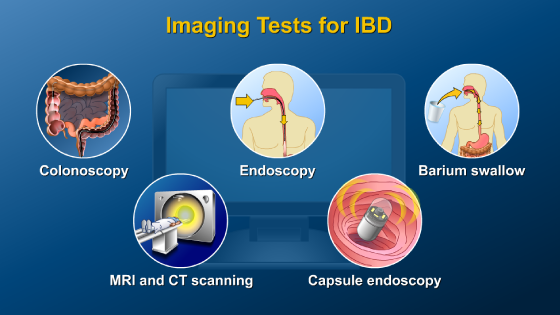

Colonoscopy with examination of the large intestine and the last part of the small intestine is an essential test for making the diagnosis of IBD and for assessing disease activity. Imaging tests also assist in the diagnosis of IBD. These include endoscopy, barium studies of the small intestine, cross-sectional imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT), and capsule endoscopy.

A colonoscopy is an internal examination of the large intestine and last part of the small intestine using a colonoscope (a flexible tool with a small camera attached to one end). The colonoscope is inserted through the anus and into the rectum and colon and then into the last part of the small intestine (called the ileum). Viewing the terminal ileum assists in the diagnosis or exclusion of Crohn’s disease.

Colonoscopy is one of the most valuable imaging tools available for the diagnosis and treatment of IBD. Small tissue samples, or biopsies, can also be done during a colonoscopy to further examine the type and extent of IBD.

Upper GI endoscopy is used to examine the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. The physician guides an endoscope down the throat - a lighted, flexible tube with a camera attached.

A barium examination allows visualization of the entire small bowel.

CT scanning is a non-invasive tool used to aid in diagnosis of IBD and to identify complications. CT combines a series of x-ray views from different angles to create cross-sectional images of the intestines.

Like CT, MRI provides cross-sectional images or “slices” of the intestines and assists in diagnosis of IBD and its complications. However, MRI uses a large magnet and radio waves to view structures inside the body. Importantly, MRI does not use radiation so the patient is not exposed to radiation.

Capsule endoscopy is a relatively new procedure during which the patient swallows an encapsulated video camera about the size of a vitamin pill. The camera transmits images to a receiver located outside the patient.

It requires no sedation, minimal preparation, and patients can resume daily activities after swallowing the capsule.

Capsule endoscopy allows viewing of the entire small bowel. It is the most sensitive way to see the lining of the small intestine. It can identify ulcerations associated with Crohn’s disease even when upper endoscopy and colonoscopy are negative.

Infrequently, the diagnosis of IBD is made when the patient is in surgery and under anesthesia.

Diagnosing IBD also includes assessing its prognosis. The prognosis of IBD is related to the likelihood of having complications or needing surgery in the future. Prognosis can be determined by clinical factors such as the age of diagnosis of the patient and the need for surgery or for steroids. But there are also newer strategies to determine prognosis which include blood tests for immune markers and genetics. In the future, these may help doctors choose treatments.

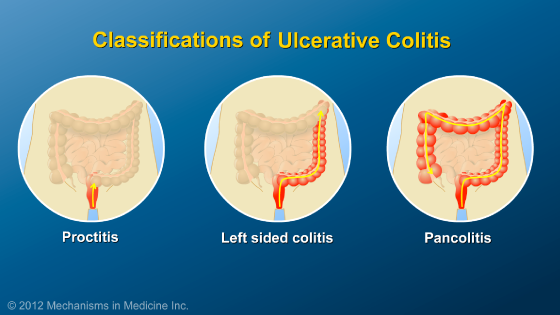

Certain proteins, called serologic markers, are present in some patients with IBD, and in some cases may be associated with disease complications. Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA) and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) are examples. pANCA have been found in patients with ulcerative colitis, and ASCA have been found in patients with Crohn’s disease.

In addition, several genes are associated with specific forms of IBD and may predict severity.

ASCA and pANCA tests, as well as certain genetic tests, are not currently used for diagnosis of IBD. However, these tests may be used to guide future choices of therapy.

Despite all these available tests, there is no single diagnostic test to definitively diagnose IBD. Occasionally patients diagnosed with one IBD type may later be reclassified to the other type. This is because classification is based on certain patterns of findings and test results most typically seen. In reality, there may be underlying and complicating factors of the disease which only evolve over time.

Click here to take our SURVEY

Your feedback is important to us! We will use your feedback to develop future areas of content about IBD which will help other patients, caregivers and families.

This educational activity has been developed by Imedex, LLC and Mechanisms in Medicine Inc.

Winner of the 7th Annual NAMEC Award

Best Practice in Collaboration Among CME Stakeholders

An Educational Collaborative with the

American College of Gastroenterology

This educational activity has been developed by

Imedex, LLC and Mechanisms in Medicine Inc.

This educational activity is supported by:

This website is part of the Animated Patient™ series developed by Mechanisms in Medicine Inc., to provide highly visual formats of learning for patients to improve their understanding, make informed decisions, and partner with their healthcare professionals for optimal outcomes.